Book: Arte sin artistas: Una mirada al Paleolítico (Art Without Artists: Exploring the Paleolithic Period). Goodreads review here.

GENERAL

+1 Well organized book with quite a lot of interesting material. It includes the whole catalogue of the exhibition as well as 24 essays on different subtopics about Paleolithic art (some of them more generic, others more specific).

+-1 There are a couple of typos/obsolete usages (such as 'homo sapiens sapiens' instead of the modern usage of 'homo sapiens'), but in general the essays also seem to be well-researched.

THE COVER and other general points about female representation

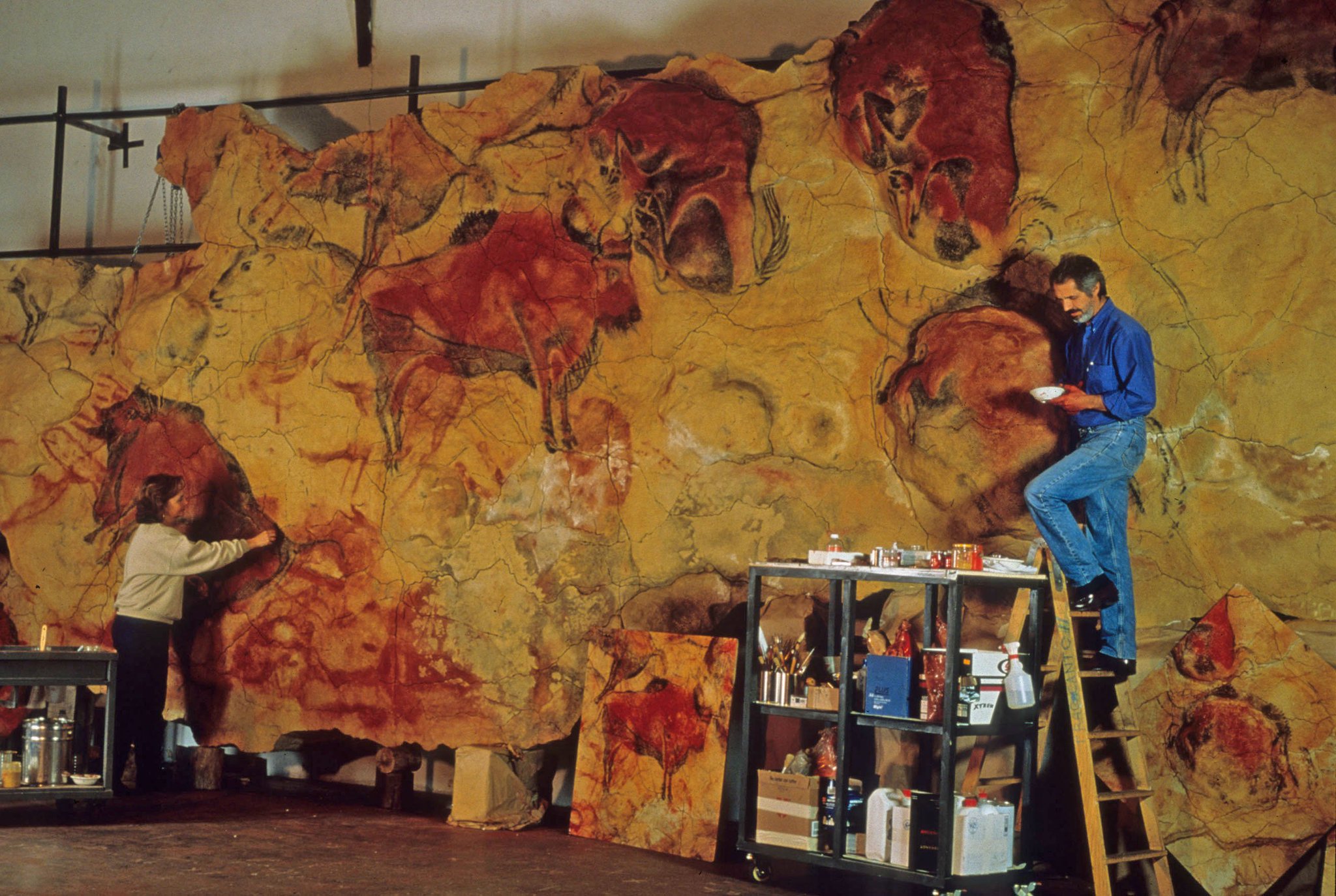

+1 I really liked that they chose to depict a female Magdalenian shaman painting part of the Altamira caves as the cover of both this book and the official cover illustration for the exhibition. History and archaeology are still male-dominated fields where female erasure and gender bias are so commonplace. There is often little female representation both in the historical subjects discussed among the people working in the fields, so this was quite a refreshing choice which I applaud.

It's rather sad, however, that the people (men, in this case) who made this decision were also worried about the controversy this cover could cause (as we know, women weren't invented until the 20th Century and those who were were only there to have children and cook, so suddenly seeing one in a prehistorical cave doing other stuff must have been quite shocking xD). They thought this choice would probably be perceived as a 'provocation', and were thus quick to assure the reader that they were not stating that it was in fact a woman who painted the Altamira cave paintings. While I agree with the fact that we cannot know for certain who it was and it's always great to be as objective as possible while listing all possible interpretations, it's also illustrative that many people, be it in the history/archaeology fields or in society in general, are usually quick to automatically assume that it was men who wrote/did/made basically everything, and that isn't generally considered as a gender bias (when it actually is), or seen as any kind of controversy or provocation :S

And also, regarding the idea that seeing a woman painting caves would be extremely far-fetched - Apart from the fact that there were at least some huntresses and women in what society sees as 'traditionally masculine' occupations in patriarchal societies with 'masculine' and 'feminine' gender roles (and we are not sure about the level of patriarchy in the Upper Paleolithic societies, either), even if most women were mainly relegated to traditionally 'female' chores and roles such as gathering, cooking, childbearing/care and textiles (not surprisingly, these roles are never questioned when assumed in all cases)...Wouldn't it make a hell of a lot of sense that women were also (maybe even mainly!) involved in cave painting and portable art, seeing as they would stay more often in the caves than the male hunters, and would potentially also have crafting tools at hand to make portable art if they were also mainly in charge of the textile area? Or that they would also have a say in the ample feminine and/or fertility representations found in Paleolithic art, given that they would be pretty familiar with their bodies and the process of pregnancy? Why would it be so far-fetched to assume that, but it's never a stretch to state that women stayed in the caves doing textile feminine stuff and looking after children in all cases?

I think it's important to note that gender bias means that people

working in the archeology and history fields often quote the 'we cannot

say this for certain' phrase when they encounter something that doesn't fit the normative view (Patriarchal with gender roles, white, heterosexual, cisgender, etc), but when it comes to

constructed gender roles and stereotypes, many are also pretty quick to

assume a lot of things which may discard more than one case, just

because it doesn't follow the established societal rules they themselves

swear by (and while we may guess in a more or less optimistic take, we

actually do not know enough about Upper Paleolithic society to state the

level of patriarchy or gender roles they had going on anyway, and this

could also vary depending on the location, etc).

Depictions of Paleolithic huntresses in Madrid's Archaeological Museum

+1 The decision to show a woman in the exhibition poster was also inspired by and meant to celebrate Spanish painter, cave art expert and art professor Matilde Múzquiz, the first person to study the cave paintings of Altamira from an artistic point of view during her PhD in 1988. She was the coauthor, alongside photographer professor husband Pedro Saura, of a large number of replicas of cave paintings for various national and international organizations.

-1 While the cover of this book and exhibition was refreshing, there is still the fact that male generics, such as 'mankind'/'man/men' instead of 'humankind'/'human(s)', are used throughout many of the essays in the book, emphasizing the male-dominated outlook and lack of inclusivity in the language used in the archaeology world (among many other places and contexts). Other essays do use 'human(kind)' consistently, though. Also, out of the 24 essays in this book (which was published in 2012), only two of them were written by women, also calling out the lack of parity we can still observe in many sectors of the academic world.

Essays discussing FEMALE REPRESENTATIONS in Paleolithic art

+1 Out of the two (out of 24!) essays written by women in this book, one of them was about female representations in Paleolithic art, exploring the Pre- and Post-Glacial periods and talking about artistic styles in quite an informative and thorough way. There are also male writers who mentioned or discussed female

representations in their essays, albeit in less depth, given as it was

not the main topic of the essay.

-1 However, one of these male authors were blatantly sexist and fatphobic in the way he tackled the issue of the Paleolithic Venus, describing them (in a very offensive and unsolicited way) as 'not particularly attractive depictions' (yes, it's massively relevant to know what the male academic of the day rates historical female depictions, sigh). He then refers to the women of the time as 'females' (red flag for dehumanizing sexism), and quips that the Venus figures are 'not reliable' because they 'obviously do not describe the females of the time in a realistic way', kinda assuming (apart from being unprofessional and sexist af) that real women with the body types usually associated with Paleolithic Venus do not exist in real life, when obviously they do :S

And furthermore, one thing which I really like about the Paleolithic Venus figures is that they include a refreshing diversity of body types and shapes, from thin to fat (all terms obviously used in a neutral way because there's nothing wrong with being fat), and, artistic stylistic choices and fertility symbolism aside, all of them can actually describe how 'real women' look like, so yeah.

Also, let us remember that women, be they real or artistic representations, do not need male validation for how attractive they are perceive to be to deserve basic respect. Apart from this, personally it blows my mind that an archeologist would not look with at least professional awe at these stunning depictions, but no, dude had to showcase his Prehistoric (lol) sexism, sigh. Thankfully, the female author of the essay focused on this topic in her essay didn't find the entitled need to evaluate their appearance and be sexist or fatphobic about it, so thank Someone about that.

|

| "But Paleolithic Venus are always exaggerated and never portray real women in a realistic way", OK my dude, OK (this is, incidentally, a photograph from the actual exhibition). |

+-1 Regarding the essay by Margherita Mussi focusing on the Venus figures and other female representations in Paleolithic art, like I said, I generally liked the information discussed in her work, but I actually don't quite agree with some of her interpretations about the association between fertility symbolism and these Paleolithic female depictions.

Enter some discussion about it -

1) The interpretation of Venus figures as fertility symbolism

|

| Venus of Laussel, an original piece from the exhibition |

I completely agree with the author's early statement in the essay that, when it comes to subjects as far back in time as Paleolithic society and art, we can't really know for certain which interpretations would be the correct ones and thus should never state these interpretations as facts. When it comes to the female representations from the Paleolithic (and especially the Venus figurines), there is more than one interpretation: From fertility, abundance and health symbols associated with religious cults and/or sympathetic magic (potentially depicting Mother/Creator goddesses), to self-portraits by female artists, to beauty ideals, to the more depressing and rather less inviting take from a feminist standpoint of seeing at least some of them as male-gazey sexualized images serving as erotica (or rather, p*rnography :/). However, the author seems to contradict herself when claiming, later on in the essay, that the Venus figures 'had nothing to do with potential fertility cults or beauty canons'. She is of course entitled to have her own interpretation on the matter, but, following her initial assertion, it's rather contradictory that she should, as it would seem, claim it as a fact :S

Personally, I disagree with her interpretation and prefer the take (which also appears mentioned in other essays in this book and is one of the most discussed) that it's highly probable that Paleolithic female representations would have had a close link with beliefs/cults, symbolism and sympathetic magic associated with the idea of fertility, health and life. I tend to think this interpretation is pretty logical (at the same time that my feminist mindset also bears in mind the negative as well as the more feminist-oriented aspects these cults can entail - which I'll discuss briefly below in a bit).

The counter-argument of the author is along the lines that it wouldn't make any sense for Paleolithic nomadic peoples to be interested in fertility cults because if a higher birth rate and emphasis on fertility were seen as important, women would be giving birth roughly every two years and would have to carry more and more weight every time in their nomadic travels, which would not be viable. Personally...I actually think it makes perfect sense that -

1) Women would have been carrying more weight than they should (both physical and in the form of childcare) because we've been seeing that kind of unequal gender roles for centuries, with women travelling and working and doing housechores with their babies on tow, so unfortunately I could also see it happening back then. Or maybe everyone in the group, including men, did 'help out' more with all the additional weight caused by new babies, and childcare could have been seen as a more collective task (it's generally believed that the pater familias family system wasn't really up and going till the Neolithic, after all). We're talking about small groups of people where daily life was often literally a question of living or dying, so tasks might have been less gendered and more equally shared given the needs of the moment, perhaps (we actually don't really know the level of gendered roles in these times, so that's also up for various interpretations, which range from completely Patriarchal societies à la The Flintstones, to a potentially too idealized equal society with hardly any gender roles, or more matriarchal-veering societies which mainly worshipped goddesses).

But my main counter-argument is that 2) In such small nomadic societies with a very low life expectancy that would probably encounter hazards and difficulties daily (from extreme weather to wild animals, poorly treated illness, to the continuous need to find and make food, clothing and shelter), I think it would not be far-fetched to assume that fertility would have been seen as very important and something celebrated and venerated as the means to repopulate the groups and keep the species alive. Also, apart from the (disputed) existing hypothesis about the understanding of pregnancy as something that wasn't directly linked with sexual intercourse in the Upper Paleolithic (a hypothesis quoted by Kate Millett in Sexual Politics, or Jean Markale in La Femme Celte, for example), contraception was most probably not going on, so women - those who could get pregnant and/or who didn't die in childbirth :S - would probably be burdened with continuous pregnancies anyway, veneration of fertility or not, so they would be probably be carrying a lot of weight in any case :S.

Also, I don't know, it really doesn't make any sense to me that for thousands of years the Paleolithic homo sapiens folks would have been drawing, painting and carving many female representations which, interpretations aside, clearly emphasize fertility symbolism if they weren't for some reason actually interested in that until the Neolithic times :S.

-Some of the screenshots containing part of the essay and my notes on this subject, in case you're interested in reading it (as usual, open in new tab for larger size)

2) Goddess feminist empowerment vs problematic patriarchal aspects about fertility cults

And I'm going to finish this post with a brief reflection on the empowering and problematic aspects I personally see when it comes to fertility cults, closely linked with both Goddess Feminism and reproductive exploitation.

The positive aspects: Firstly, when it comes to the Paleolithic Venus figurines and the representation promoted by Goddess Feminism in general, I do like how there's a positive diverse portrayal of female body types, something which can be linked with the modern body positivity movement and fight constraining Patriarchal beauty canons.

Then there's the important fact that these historical female representations often linked with goddesses and the 'Divine/Sacred Feminine' have also served to help visibilize the female body and sexuality, often invisibilized and severely stigmatized since centuries past by Patriarchal societies, especially by the cultural influence of Abrahamic religions (for clarification, I note that, while I'm mainly referring here to the gender binary, there are also depictions which are non-binary/dual/androgynous/etc in the area of goddesses, mythology and its associated cults and movements). Goddess Feminism, which draws its influence and inspiration on these historical female depictions and pagan cults, and emerged mainly in America, Western Europe, Australia and New Zealand as part as the Second Feminist Wave in the 1970s, has also helped promote female empowerment and representation in more than one respect. However, it's also worth nothing that the movement can also have problematic aspects, such as more essencialist and/or traditional gender role views, or the overt idealization and promotion of fertility mindsets which are way too linked with traditionally patriarchal reproductive exploitation.

Finally, I also like the fact that these movements often focus on women owning their naked bodies and sexuality in a way that's not instantly catering to the male gaze or desire, and I actually find the Paleolithic Venus refreshing, for example, because I can often see it as diverse female nudity that doesn't seem to be there mainly for the male gaze (of course, this could be massively idealized if we take the p*rn interpretation into account :S, but at least these female depictions have served to promote all that, so there's still that disregardless of the original intention of the figurines).

The problematic aspects: On the other hand, I can also criticize quite a lot of things about fertility cults, which can be closely linked with reproductive exploitation, one of the main roots of patriarchal oppression, and also present in apparently 'matriarchal' societies that worship goddesses, as we can see in The Mists of Avalon, for example.

Female depictions emphasizing fertility symbolism can also be seen as dehumanizing and sexist by seeming to reduce (cis) women to their reproductive ability and sexual characteristics. (Note: cis

women are the main demographic in this matter, but of course trans men,

intersex people and non-binary afab people would also be targeted - and most probably also misgendered :S -

by oppressive fertility mindsets. And it's also worth mentioning

that an incorrect treatment of Goddess and neopagan feminism can also become essentialist

and transphobic against both trans men and women as well). The fact that we know that male

graves are way more common in the Paleolithic findinds than female

ones, while female depictions (often emphasizing fertility) massively

outnumber male artistic representations is another thing that could

suggest that Goddess feminist movements could have idealized these female

representations as an era of greater female independence and empowerment, and maybe the reality was that the significance behind the

numerous Paleolithic female representations could be thus severely

limited to their perceived societal use as reproductive vessels for the

perpetuation of the species :S. This idea can also be seen in modern feminist shows such as The Handmaid's Tale, which focuses on Patriarchal oppression and revolves around the sexual and reproductive exploitation of women in a misogynistic theocracy, and which has made use of fertility goddess symbolism as well as Christian material in order to portray the reproductive exploitation of Gilead.

It is maybe a bit unclear whether the original idea was to show how former more feminist-coded Goddess imagery, especially in the 1970s with its association to feminist characters such as June's mother Holly, was made more regressive and oppressive by Gilead. The problematic points of neopagan fertility mindsets still remain, though, and I think it is fitting to show Gilead also appropriating that imagery alongside Christian patriarchy, because firm believers in the utter female empowerment of Goddess feminism often fail to be critical of the fact that neopagan and Goddess mindsets, while empowering and refreshing in some aspects and especially against more blatantly patriarchal monotheisms, are also deeply problematic and still misogynistic and non-inclusive in others, and have also oppressed women historically for reproductive exploitation purposes, as well as sometimes also reinforcing gender roles and the gender binary. So I personally get why Margaret Atwood (in The Testaments, mostly) and the Handmaid's Tale series creators would also use Goddess-y religious imagery as a way of portraying reproductive exploitation.

In spite of these more considerably problematic aspects, I think that one of the main reasons why the feminist imagination has revolved so often around Mother Goddesses and these historical female representations so linked with fertility is that it can be seen a very refreshing change opposed to, for example, the total stigmatization and invisibility of the feminine in the patriarchal Abrahamic world and other patriarchal cultures and religions. While the idea of Goddess worship and the Divine Feminine can be idealized in more than one case, ranging from the more naïve to the more problematic (exclusionary or authoritarian), these depictions, disregardless of their original intention, have certainly helped and can still keep helping to promote female empowerment and representation. Still, we must remain critical of the flaws and problematic aspects as well.

Hope you enjoyed this essay, see you hopefully soon-ish with more historical and/or feminist material(or preferably both xD)!

VS

VS