| Ancient Greek women doing house chores (author unknown to me) |

A couple of days ago I visited the local National Archaeology museum again, so today's post will be about Ancient Greece, and I'll be writing about the intense gender inequality of ancient Greek society, mostly by commenting the exhibit quotes and descriptions.

The exhibit descriptions seem to have been written, in general, with the aim of critisizing the intense misoginy and strict gender binary of the ancient Greek society - Which is a good thing, sexism in history should be taken into account and critisized way more often. Especially when we're dealing with a society that's often way too romanticized and where women were recluded to the home, stripped of practically any human rights and relegated to the traditionally 'feminine' roles of house activities, making themselves beautiful for their husbands, and child-bearing.

But of course, nothing is perfect: The first thing I'd like to critisize about the Greek area of the museum is that there are some examples of sexism by omission in the Spanish versions of some of these descriptions, by referring to the whole of humankind with only male terms: 'Man' vs 'Human', two words which shouldn't be synonyms. 'Man' used in this context is exclusive, seeing as there's no mention of women in the wording. Also, they take gender into account, which isn't necessary, either (the term 'human' doesn't include a gender connotation) - Not only is this excluding women, but people who identify as agender, non-binary and genderqueer as well. And lastly, it introduces ambiguity, because sometimes 'man' used in this context could be read as 'male' - and in a description about gender roles, ambiguity is even the more probable.

|

|

| Sexism by omission and sexist language: The problem of 'man' as a general term (Source) |

Another thing I'd like to comment about the Greek exhibit descriptions is that sometimes the texts don't seem to critisize the misogynistic and gender biased aspects of the society as strongly or non-ambiguously as I think they should, and this could be problematic. Given that some statements seem to be written in a purely neutral way, or simply devoid of any direct criticism, they could be interpreted quite literally by people who don't exactly come to the museum to question their patriarchal-based and gender-biased upbringing. Like another blogger said here, people could easily read quotes such as 'I am grateful for being born a man and not a woman', displayed devoid of connotations against the inherent sexism of the quote, as a continued assertion of male superiority rather than as a feminist criticism of the sexism among the Ancient Greeks. In these cases, I think we need direct criticism, not subtlety.

- The sexism of the Greek gender binary

Entering into the Greek section of the museum, we are greeted by a statue of Apollo accompanied by this quote (translation below):

por ser hombre (un ser humano) y no animal,

por ser varón y no mujer,

por ser griego y no bárbaro

(Diógenes Laercio I, 34)"

(Sobre la tradución española: La palabra 'hombre' es usada incorrectamente en lugar de 'ser humano', ejemplo de sexismo por omisión en el lenguaje. Además, en el original griego se diferencia entre 'humano' (ἄνθρωπος, "ánthropos"), la palabra usada en esta cita, y 'varón' (ἀνήρ, "anḗr"). En la traducción inglesa (ver abajo), se traduce correctamente como 'human being'.

Por otro lado, la referencia a la obra está inacabada: Vida de los filósofos más ilustres, I, 34)

"Hermippus in his Lives refers to Thales the story which is told by some of Socrates, namely, that he used to say there were three blessings for which he was grateful to Fortune: "first, that I was born a human being and not one of the brutes; next, that I was born a man and not a woman; thirdly, a Greek and not a barbarian." [34] "

(Source: Tales de Mileto (ambiguo) citado por Diógenes Laercio en Vida de los filósofos más ilustres I, 34 /Thales of Miletus (ambiguous) quoted by Diogenes Laertius in Lives of Eminent Philosophers, I, 34)

And the Greek original:

(Source: Tales de Mileto (ambiguo) citado por Diógenes Laercio en Vida de los filósofos más ilustres I, 34 /Thales of Miletus (ambiguous) quoted by Diogenes Laertius in Lives of Eminent Philosophers, I, 34)

And the Greek original:

Ἕρμιππος δ᾽ ἐν τοῖς Βίοις εἰς τοῦτον ἀναφέρει τὸ λεγόμενον ὑπό τινων περὶ Σωκράτους. ἔφασκε γάρ, φασί, τριῶν τούτων ἕνεκα χάριν ἔχειν τῇ Τύχῃ: πρῶτον μὲν ὅτι ἄνθρωπος ἐγενόμην καὶ οὐ θηρίον, εἶτα ὅτι ἀνὴρ καὶ οὐ γυνή, τρίτον ὅτι Ἕλλην καὶ οὐ βάρβαρος. 16 [34] (Source)

Alongside the statue of Apollo and this magnificently narrow-minded quote, a gem from ancient times indeed, we find texts seemingly critisizing the quote by commenting on 'men', 'women' (both the traditional role and the antithetic role of the Scythian Amazons in 'mythology'), 'animals', and 'foreigners':

"El hombre:

El varón define su identidad a través de conductas que entiende como virtudes. Debe ser agresivo, competitivo, autocontrolado, sociable y respetuoso con los dioses, excelente en suma. Los inmortales, espejo del comportamiento masculino, encarnan estas virtudes en su más alta expresión."

"Men:

The male defined his identity through forms of behaviour which were regarded as virtues: He was supposed to be agressive, competitive, self-disciplined, sociable and respectful to the gods. In sum, he was to be excellent. The immortals - the mirror of male conduct - embodied these virtues in their highest form of expression."

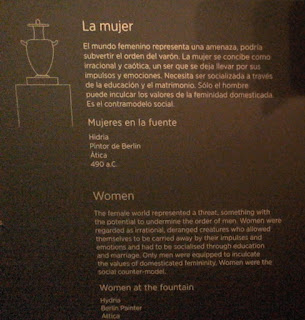

"La mujer:

El mundo femenino representa una amenaza, podría subvertir el orden del varón. La mujer se concibe como irracional y caótica, un ser que se deja llevar por sus impulsos y emociones. Necesita ser socializada a través de la educación y el matrimonio. Sólo el hombre puede inculcar los valores de la femineidad domesticada. Es el contrapunto social."

"Women:

The female world represented a threat, something with the potential to undermine the order of men. Women were regarded as irrational, deranged creatures who allowed themselves to be carried away by their impulses and emotions and had to be socialized through education and marriage. Only men were equipped to inculcate the values of domesticated femininity. Women were the social counter-model."

"Las Amazonas:

Mujeres guerreras que viven en los confines orientales del mundo, las Amazonas rechazan vivir bajo el dominio masculino. Representan la alteridad absoluta frente a la mujer sometida y a la convivencia ordenada de la sociedad griega. Son mujeres salvajes y bárbaras. Son el contramodelo mítico."

"The Amazons:

The Amazons were female warriors who lived at the eastern ends of the world and refused to live under male domination. They represented absolute otherness, the opposite of domesticated women and the orderly coexistence of Greek society. Wild and barbaric, these women were the mythical counter-model."

"The scene depicts the struggle between Theseus, the young Athenian hero, and Hyppolita, Queen of the Amazons. During the years of Pericles' government, this legend was used to simbolize the triumph of civilisation, embodied by Athens, over savagery."

I choose to read phrases such as 'wild and barbaric', 'the orderly coexistence of Greek society' and 'the triumph of civilisation over savagery' as sexism that it's being critisized, but it's highly ambiguous and very poorly worded and expressed, with the problems I was talking about at the beginning of this post: People who don't come to the museum to question gender roles and sexist mindsets could perfectly interpret phrases such as these as not being critical at all, and could exit the museum thinking that 'Yes, the Amazons were wild, barbaric women because they didn't want to obey or be with men, in the orderly Greek society (because gender roles are traditional, have been there for centuries, and rock my socks), and that makes them barbaric and savage. Also, they're wild and barbaric because they were warriors, which is a monstrosity because women aren't supposed to be warriors, dude! They should be having children and staying at home like the civilized and orderly Athenian women!' Don't tell me we don't have way too many individuals in our modern 'orderly society' who still think like this.

- Daily life and gender roles:

|

| Ancient Greek women and traditionallly 'feminine' roles: Weaving and making clothes, keeping beautiful for the males (Author unknown to me). |

Most of the exhibits were focused on daily life and the often rather ambiguously critisized gender roles having to do with education (the men's world), feasts and parties (the men's world), the home (the women's world), marriage (the women's world, and the turning point of her 'career'), children (the women's world) and death (more or less gender neutral, although the women are the ones who should be lamenting). And like I said before, the descriptions are generally either purely neutral, seemingly critical but ambiguosly worded, and, only sporadically, directly critical.

This more feminist approach can be found at the very end of the exhibition, at the 'touching objects' area (which is also aimed towards blind people), and very clearly reads "Female invisibility vs Male visibility":

(Female invisibility/ male visibility)

"Las principales actividades de la mujer ateniense tenían lugar en el ámbito del hogar. Bajo la tutela del esposo, después de haber estado bajo la de su padre, se encargaba del gobierno de la casa y de la educación de sus hijos mientras eran pequeños. Rara vez salía del hogar.

Como contrapunto, y frente a esta invisibilidad social de la mujer, el hombre participaba plenamente en la vida pública. Recibía ya desde la infancia una esmerada educación, participaba en el gobierno y en la defensa de la ciudad y podía relacionarse con sus iguales en el gimnasio, el ágora o el banquete, ámbitos específicamente masculinos."

As a counterpoint to this female invisibility, men took an active and full part in public life. They received from their childhood a thorough and careful education, participated actively in the government and the defense of the city, and were able to socialize with their equals in the gym, the agora or during feasts, all areas which were exclusively masculine."

My (free-ish) translation:

"The main activities of the Athenian woman took place at home. First under the guardianship of their fathers and then of their husbands, they were supposed to take care of the house and of the children's education while they were young. They seldom left the house.As a counterpoint to this female invisibility, men took an active and full part in public life. They received from their childhood a thorough and careful education, participated actively in the government and the defense of the city, and were able to socialize with their equals in the gym, the agora or during feasts, all areas which were exclusively masculine."

Now, I think this is adequately worded as being informative and historically objective, but also critical ('female invisibility', 'male visibility', 'they seldom left the house', 'as a counterpoint men took an active part in public life', 'were able to socialize with their equals',...). This doesn't give the ambiguous vibe that maybe gender roles are cool and acceptable because it 'the ways things were (and are)' and 'part of an orderly society'.

More excerpts from the gendered Ancient Greek daily life shown in the exhibit

"El banquete:

Las relaciones sociales de los varones griegos giran en torno a la bebida en común, la fiesta del simposio. Dentro del ocio colectivo masculino, el simposio reúne a varones de una misma clase social para compartr amistades, intereses y placeres. (...) Las reuniones se prolongan hasta el amanecer, entre cantos, poesías, charlas de filosofía y política. Las heteras, cortesanas, amenizan el banquete. Ellas son también parte del ocio masculino. (...)"

"The banquet:

Social relationships between Greek men revolved around drinking in fellowship, at the symposium. Part of the male collective leisure activities, the symposium gathers men of a same social class in order to share friendships, interests and pleasure. (...) The reunions go on until dawn, amid songs, poetry, philosophy chats and politics. The hetairai, courtesans, liven up the banquet. They are also part of men's leisure."

"The banquet:

Social relationships between Greek men revolved around drinking in fellowship, at the symposium. Part of the male collective leisure activities, the symposium gathers men of a same social class in order to share friendships, interests and pleasure. (...) The reunions go on until dawn, amid songs, poetry, philosophy chats and politics. The hetairai, courtesans, liven up the banquet. They are also part of men's leisure."

"La buena esposa conviene que mande en los asuntos de puertas adentro de la casa...sin prestar atención a los asuntos públicos...Una esposa de vida ordenada debe considerar que las normas de su marido le han sido impuestas como ley de su vida."

(Pseudo-Aristóteles, Económico, 140-1, Rose)

"A good wife must only govern those matters from within the home...without minding public affairs...A wife with an orderly life must take into account that the rules of her husband have been imposed to her as an inevitable fact of life."

"La boda:

La boda es el rito de iniciación a la vida adulta para las mujeres griegas y la consolidación de su destino social. Representa el abandono de la infancia, de su estado de doncella, y el ingreso en el mundo ordenado y reglamentado del varón. Su papel será dar hijos legítimos y perpetuar la familia. Las etapas de la ceremonia escenifican este cambio: la ofrenda de los juguetes infantiles, el baño ritual, la espera y el rapto nocturno por el novio, el alegre cortejo en carro nupcial hasta su nuevo hogar, en el seno familiar del marido. Allí se despojará de su velo de pureza. El ajuar, la dote y los regalos materializan el lenguaje simbólico y el prestigio social del momento culminante de la vida femenina."

"The wedding:

Marriage was the rite of passage through which a Greek woman entered adult life and confirmed her future social fate. It represented the end of her childhood and maidenhood, and her induction into the rigid, orderly world of the male. The woman's purpose in life would be to bear legitimate offspring and ensure the family's continuity.

The different stages of the marriage ceremony enacted this transition: the offering of children's toys, the ritual bath, the wait and the bride's nocturnal abduction by the groom, the festive procession in a nuptial cart to her new home, where she would be surrounded by her new husband's family and the veil symbolising her purity would be removed. The dowry and wedding gifts expressed the symbolic importance and social prestige of this moment, the high point of a Greek woman's life."

The worrying ritual of 'abducting' the bride glorifies sexual assaults, violence against women and lack of equality in a relationship. The inspiration for this troubling and misogynistic ritual comes from the abduction and rape of the poor Goddess Tethys by the jerk and scumbag Peleus, a human who hasn't been taught anything about consent (we also know that a society is deeply patriarchal when not even goddesses are safe from being assaulted by male humans):

| Because abducting and sexually assaulting a woman is so romantic, and something to glorify and to have as the ideal model for every wedding. Naturally. |

"El mito de las bodas de Tetis y Peleo:

El rapto de Tetis en presencia de sus hermanas, las Nereidas, es el preludio de la boda más gloriosa de la mitología griega. (...) La imagen idealizada del mito, frecuente entre los regalos nupciales, se utiliza como referencia modélica para la novia ante tan decisivo tránsito (sí, muy "romántico" todo)."

"The myth of the wedding of Tethys and Peleus:

Peleus abducted Tethys in the presence of her sisters, the Nereids. Afterwards the lovers (ahem...lovers??) celebrated the most glorious wedding in Greek mythology. (...) The idealized image of this myth, commonly featured on wedding gifts, was upheld as a model for the bride in this life-changing transition (oooh, I'm being symbolically abducted, it's soooo romantic!)"

"Las edades de la vida:

El ciclo vital, desde su comienzo, el parto y la infancia, hasta el final, la vejez y el llanto por la muerte, son tareas de exclusividad femenina. La vida se gesta y se cierra en el oikos.

El cénit de la existencia en Grecia es la juventud. En ella se alcanza la más perfecta expresión de la femineidad y la masculinidad. Dos destino diferentes se diseñan para los hijos: la niña, ya mujer, regresará al oikos; el niño, ya hombre, se integrará como ciudadano en la polis.

Las distintas etapas de la vida están marcadas por ritos de tránsito, protegidos por Ártemis y Apolo y regulados por códigos sociales y religiosos que sancionan los distintos grupos de edad y de género."

"The stages of life:

The circle of life, from childbirth and infancy to old age and the sorrow of death, was the sole prerogative of women. Life as conceived and came to an end inside the oikos.

In Greece, youth was the zenith of existence, the most perfect expression of femininity and masculinity. Two different fates were reserved for children: The girls, on reaching womanhood, would return to the oikos, while the boys were destined to become citizens of the polis on reaching manhood.

Each stage of life was marked by rites of passage, protected by Artemis and Apollo and governed by social and religious codes that distinguished each age group and gender."

- Clothing

It's also worth mentioning that, while Greek male depictions are often of men with bare torsos, bare legs or fully nude, bare female torsos in the exhibit were pretty rare, mostly associated with female idols or the marriage section (the case of the female torso above). Greek women's clothing was actually very restrictive (patriarchal 'modesty' mindset acting as a way to control and repress women's autonomy and sexuality), something that many people, accustomed to seeing female nudes in Greek statues and idealized depictions of Greek fashion, may not be familiar with. Short tunics were only acceptable in places such as Sparta, ankle-length tunics were the norm. Hairstyles where the hair was partially or completely covered by a cloth or headscarf were also common (open hair or even loose strands were hardly worn), and women, especially married women, had to cover their head at least partially, and wrap themselves in an himation (mantle) when going out - when they were actually allowed to be out, that is. Not dissimilar to the idea of today's burkas, the himation is 'a garment of decorous modesty' which disguised the shape of the woman's body in public, and which Hetairai also used as 'provocation' (in the same way veiling is used in 'exotic dancing' in the Near East). This is quite a different idea from the idealized woman wearing the light tunic that we're so accustomed to seeing in Neoclassical and modern depictions of Greek culture, and not at all dissimilar from the religious-based head and body coverings typical of Patriarchal Monotheistic (and also polytheistic) religions. (There's a section on male and female Greek clothing in the pdf below)

| Bronze statuette of a veiled dancer wrapped in an himation. |

"The Himation is a kind of cape, which can cover the whole body, if necessary. Especially adult, married women use it to cover the head, the shoulders, and the shape of the female body in public. (...) The Himation is a sign of social status and morals, similar to the Palla used later by Roman women." (Source)

"Outside the house, the hair is always put up and made into a bun on the neck or the back of the head. Additionally, the hair is held back by a band wrapped around the head or by a bonnet/hairnet to keep the hair in place. Very few women are depicted with loose strands or even open hair." (Source)

And to finish the exhibit, there were some images of the goddesses Athena and Ártemis as a refreshing change from these enslaved and embowered Greek women. Only certain mythological female characters such as these couple of goddesses (who are Pre-Hellenic anyway) are allowed to take some of their own life choices, get involved in crafts, learning and martial arts and remain unmarried while hunting in the woods or taking arms, though. Unfortunately, empowered goddesses in Greek mythology aren't the proof we need to think that Ancient Greek women could do such things in real life.

|

| Janet Stephens' Grecian hair tutorials show how the hair was often partially or completely covered by cloths, as part of Ancient Greece's modesty mindsets for women. Even if the hair was not covered by a cloth/headscarf/hairnet, women usually had to cover their hair with an himation when going out, and it was rare to have loose strands or open hair, as opposed to the idealized depictions that we are accustomed to seeing in statues, 18th and 19th Century art, and movies.

"Greek women were expected to fully cover their bodies. For instance, a woman would not gird up her chiton like a man and display her legs in public." (Source)

|

To finish this post, I'd like to share an excerpt of The Ancient City, by Peter Connolly and Hazel Dodge, about the (oppressive) role of women in Ancient Greek society. My book is in Spanish, so Spanish translation only, sorry!

Cómo me gusta!!! A un "<3" y a una carita ":)", le añades admiración y satisfacción por ver un trabajo bien hecho y que merece la pena hacer.

ReplyDeleteGracias miles ^^ <3!

DeleteThat was a good post! Very nicely done. And thanks for taking the time to write it! :)

ReplyDeleteI wonder if they saw the irony in having a venerated goddess like Athena and at the same time regarding the women who acted that way as something bad and negative. Maybe Athena didn't count as a "real" woman because she was a goddess, and trying to imitate the gods was sometimes bad?

Belated thank you! :)

DeleteThat was probably one of the reasons, yes (and that's why sometimes the fact that a culture has interesting goddesses doesn't necessarily mean thay the women were as well off in real life). Most of the goddesses in the Greek pantheon were either Pre-hellenic or from the Near East, anyway, and many of them were accordingly diminished in order to fit the patriarchal Greek society better (Hera, Amphitrite, Gaia and other goddesses being paired with abusive and cheating husbands when they were initially lone mother goddesses, Artemis being initially the Sun goddess but getting a brother who became the Sun god instead, single goddesses such as Athena and Artemis being portrayed in a bad light sometimes because of their non-traditional aspects,...).

Ooooh, I didn't know those things. Thanks a lot! :)

DeleteYou're welcome :)! I love learning about goddesses and mythology :)

Delete